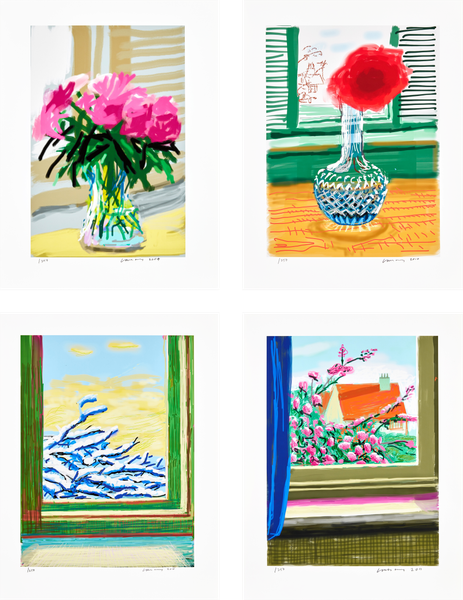

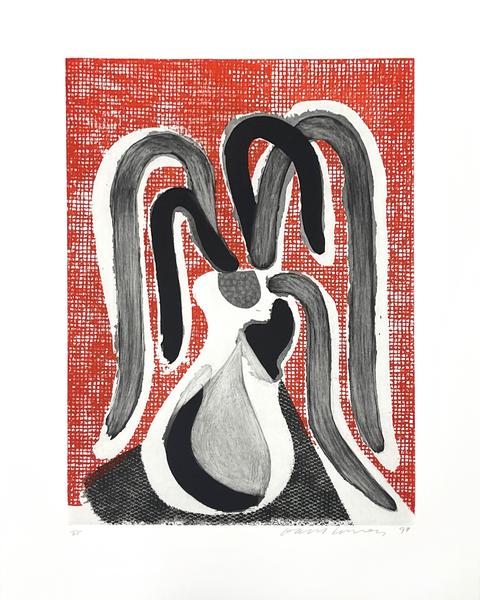

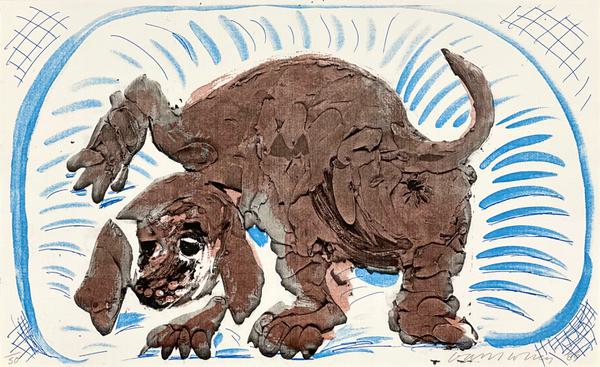

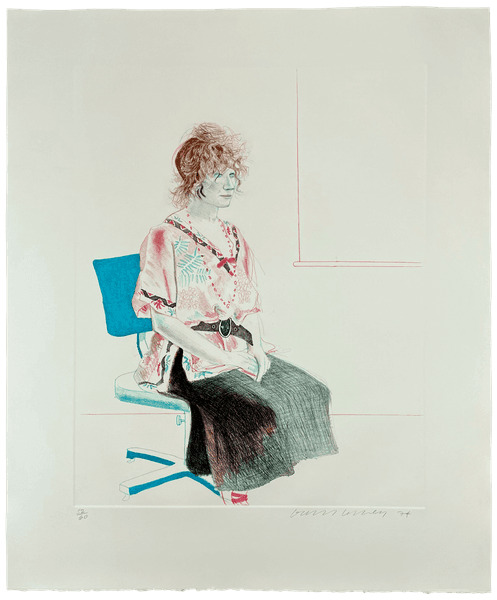

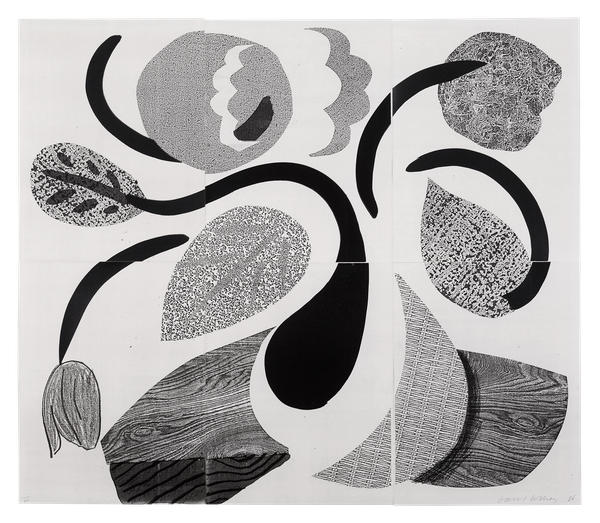

Stanley in a Basket, October 1986

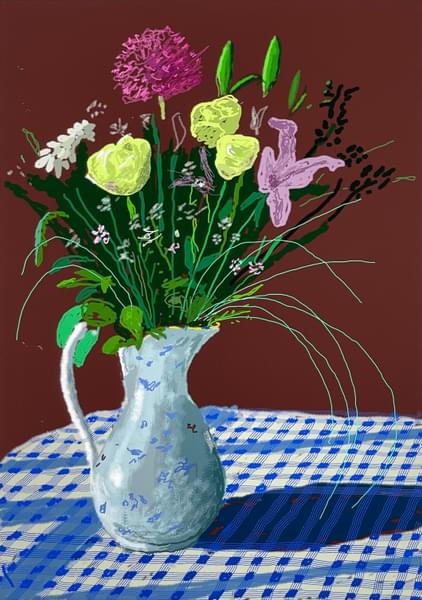

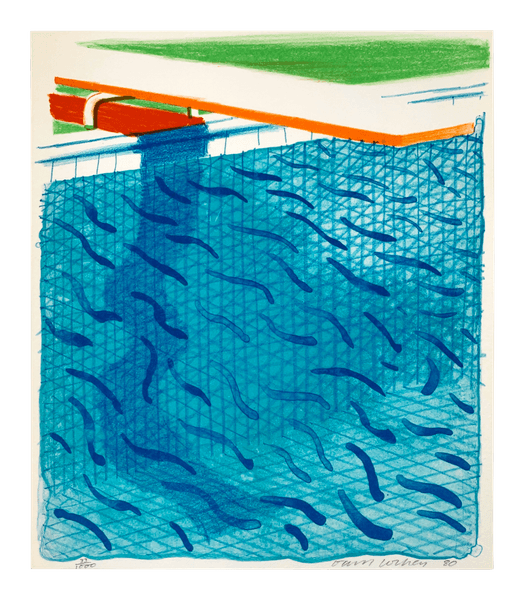

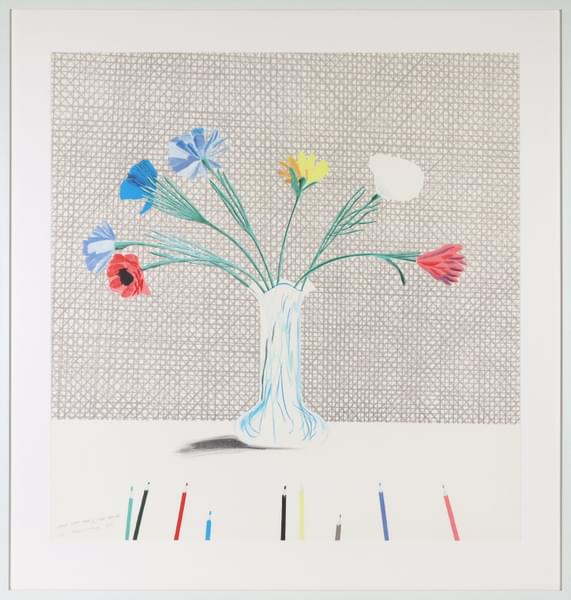

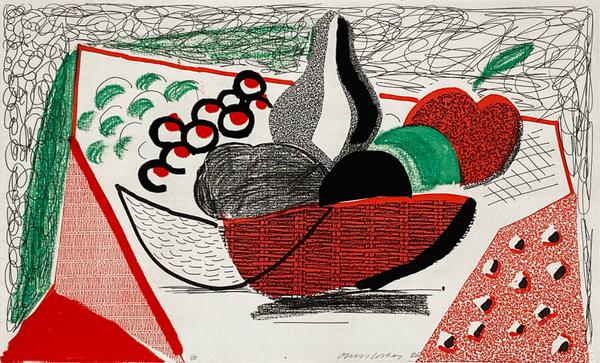

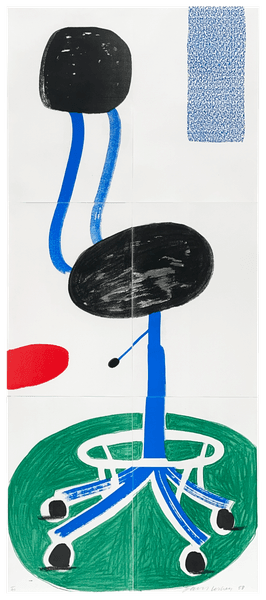

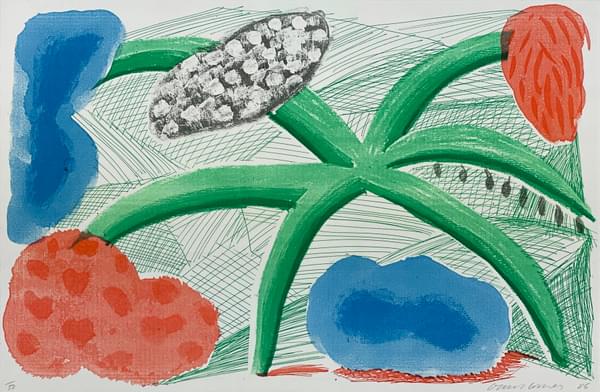

David Hockney's investigation into the newly invented technology of colour photocopying in 1986, which resulted in the series Home Made Prints, typifies the artist's restless drive and skill in invention over 6 decades. Hockney, fascinated by the new devices, deconstructed the multi-colour printing capability of these office "cameras", and created a series of works, each made by the artist himself with no proofs. Puzzled by the flatness of colour photocopies generated by the early xerox machines, he set out to see if they could be improved upon and soon realised that the colours sharpened if printed one coloured layer at a time. He demonstrated that prints made from these machines with care, attention and an enquiring skill are vastly superior to their products when used as intended, i.e. to make a coloured copy in one single pass. This demonstration, and this typical mode of enquiry, defines completely what makes Hockney one of the greatest artists working today.

In May 2021 Sotheby's New York sold a complete set of the 33 Home Made prints to have been included in the 1986 André Emmerich catalogue for a record price of $963,800. Stanley in a Basket, October 1986 was printed by Hockney too late for inclusion in the catalogue, however handwritten notes from a copy of the catalogue in the archives of LA Louver state "8 additional ones...brought in last minute before opening."

A PRISTINE example of this rare print. Never before framed, the print has been kept in a print drawer for the entirety of its life, having fresh and bright colours precisely as printed.

-NOTES ON THE TECHNIQUE by DAVID HOCKNEY- from the self-published catalogue to accompany the exhibition at Andre Emmerich's New York gallery, Zurich, 1986.

It is difficult to be spontaneous making a colored print. The necessity of drawing in layers that will fit together causes this, and techniques that help the artist with this problem have been very few, and artists have had to accept a certain stiffness as the price for the colors.

ln 1973 Aldo Crommelynck, in Paris, explained to me a method he had devised for Picasso to get round this problem in colored etchings. His explanation and demonstration was very clear and made me abandon my plans and experiment with it. I later used the technique in a series of 20 etchings inspired by Wallace Steven's poem "The Man with the Blue Guitar”.

My own photographic experiments made me look into cameras and what they were really doing, making me realize that an office copying machine was a camera that confined itself to flat surfaces. It never attempts to depict space. That the machine is also a printing press we knew, but never regarded it as a good one. Yet thinking about these machines for awhile before I first played with them two things occurred to me: that there is no such thing as a copy and that there is no such thing as a bad printing machine. (Only bad printers.)

Of course in an office, it is used for copying messages; the slight variations in the marks from one to the other is not noticed because the content of the readable message is what is important.

I began experimenting with a friend's machine in February of this year and within an hour realized my hunch was right. They were fascinating printing machines, indeed they were a totally new kind of printing that offered the artist new areas and possibilities.

First let me talk about it as a camera. I quickly realized that it was also a new type of camera, that had in effect moved right up to the surface (two dimensions), narrowing the space between the lens and the object. It photographs one for one, same size. This might seem at first a trivial point, and it took me a while to realize what it might be doing - was this space (or lack of it) important? Was it visible? I came to the conclusion that it was visible after studying the effects of textures produced by the machine. The most important aspect of the machine though seemed to be that this "new space" was combined with a totally new form of printing, very high-tech.

It is new in this way: it prints from paper to paper, it prints totally dry, and the "ink" is put on the paper electronically. For the artist there are great advantages here. First, printing from paper to paper means that the original marks can be made on the same kind of paper one prints on. This seemed to me to remove a layer. For instance a wash in a lithograph is made by dipping a brush in touche and laying it on a zinc plate, a stone, or mylar. Now the way a brush behaves on these surfaces is different from the soft absorbent surface of paper, the way the wash dries is different-on paper it is through absorption and evaporation, on the hard surfaces it is evaporation only, so the marks printed on paper from paper seemed more direct. (A lithographic wash on paper is an illusion of a paper wash - it was made on metal.)

Secondly, printing totally dry enables one to put layer upon layer immediately (in some prints here as many as twelve); and thirdly, the way the "ink" is put on the paper is totally new. It is not an "ink" in the normal sense, but a powder - called "toner" in the office copy business. It is a powder fused onto the paper by a heat process. Now all printing inks begin as powder (pigments) and with the addition of oil become inks that can be rolled into a thin film. But oil is a reflective surface, so however little there is left in the ink on the paper, a slight reflection will occur. With black this is very noticeable, but here I noticed how beautiful and dense the black was especially on the larger Kodak machine. It seemed to me it was the blackest and most beautiful black I had ever seen on paper. It seemed to have no reflection whatsoever, giving it a richness and a mystery almost like a “void”.

I used three different machines, first a Canon P.C.25, then a Canon N.P.3525 and lastly a Kodak Ektaprint 225F.

The images are made like one makes any color print. Each separate color is drawn onto a separate piece of paper (as each color is printed separately in the machine). I had experimented with methods of making marks and how the machine "sees" them, discovering that some marks are more easily translatable by the machine than others - I assume one of the subjects of these prints is the joy of discovering a new medium.

I attempted to get 60 "identical" prints, not always achieving this number, as the complicated layering made me lose many, but whatever number I finished up with is all there is. I printed them all myself (it seemed to me that the drawing process and printing process fused) therefore my numbering system is quite simple. If I finished up with 45 then they are numbered one out of forty-five, two out of forty-five and so on - there being no "artist proofs," "printer proofs," "roman numeral proofs," or any kind of proof that is not involved in the stages of making the print.

Now one might ask, couldn't the machine make a copy of the print? Well of course it can attempt to, but the results look like office copies usually look. The reason here is that naturally the machine cannot copy its own layers. That would be the equivalent of going backwards in time and this is not yet possible even in high-tech.

There are amusing reversals happening. The pictures in this book are photo reproductions of prints from an office copier, as such they cannot have the physicality of the color on the prints, in short they are not as good. Of course you can make a copy of the reproduction in this book, and it too will be different. It seems to me that it's nice to know we have not yet reached "the age of mechanical reproduction" -and it's still love and care that makes a difference, even with machines.

Stanley in a Basket, October 1986

- Artist

- David Hockney (b.1937)

- Title

- Stanley in a Basket, October 1986

- Medium

- Home made print on 120g Arches rag paper executed on an office colour copy machine

- Date

- 1986

- Size

- 8 ½ x 14 in : 21.6 x 35.6 cm

- Edition

- From the edition of 50, signed, numbered and dated by the artist and having the studio blindstamp lower right

- Printer

- Printed by the artist

- Publisher

- Published by the artist

- Literature

- Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, and Tankosha Publishing Co., Ltd., Publ., David Hockney Prints 1954-1995, 1996, cat. no. 318, p.172, (col. illus.)

- Reference

- AC21-34

- Download PDF

- Status

- Available

Available Artists

- Ancart Harold

- Andre Carl

- Avery Milton

- Baldessari John

- Barnes Ernie

- Brice Lisa

- Castellani Enrico

- Crawford Brett

- Dadamaino

- Dávila Jose

- de Tollenaere Saskia

- Downing Thomas

- Dyson Julian

- Elsner Slawomir

- Freud Lucian

- Gadsby Eric

- Gander Ryan

- Guston Philip

- Haring Keith

- Held Al

- Hockney David

- Katz Alex

- Kentridge William

- Knifer Julije

- Le Parc Julio

- Leciejewski Edgar

- Léger Fernand

- Levine Chris

- LeWitt Sol

- Marchéllo

- Mavignier Almir da Silva

- Miller Harland

- Modé João

- Morellet François

- Nadelman Elie

- Nesbitt Lowell Blair

- O'Donoghue Hughie

- Perry Grayson

- Picasso Pablo

- Pickstone Sarah

- Prehistoric Objects

- Quinn Marc

- Riley Bridget

- Ruscha Ed

- Serra Richard

- Shrigley David

- Smith Anj

- Smith Richard

- Soto Jesús Rafael

- Soulages Pierre

- Spencer Stanley

- Taller Popular de Serigrafía

- The Connor Brothers

- Turk Gavin

- Vasarely Victor

- Wood Jonas